My every-day wristwatch is a Seiko 5: a self-winding mechanical watch that’s water-resistant and has day and date complications, a see-through back so you can appreciate the coolness of its mechanical movement, and the distinct feature of being extremely cheap– when I got it five years ago, I paid about $90 CAD. Although mechanical watches are much cooler than quartz crystal watches, they’re also far less accurate and from time to time they need to have their timing calibrated.

Unfortunately, having a watch professionally serviced is kind of expensive. Getting my Seiko 5 looked at would likely cost far more than what I paid for the watch in the first place, so, a while ago, when my watch started losing a minute or so per week, I decided to figure out how to regulate it myself.

The timing of almost all mechanical watch movements is regulated by adjusting the tension on the hairspring, which controls the rate at which the balance wheel oscillates between its tick and tock swings (check out this amazing blog post for more about watch movements). On my watch’s 7S26C movement, this is done by gently adjusting the regulator lever so it points closer to either the + or - sign, depending whether you want the watch to tick faster or slower.

Since my watch was losing time, I needed to push the lever closer to the + sign. I opened the case, carefully pushed the lever in the right direction with a matchstick (if you ever try this, don’t use magnetized metal as it can damage the movement), screwed the case back back on, and reset the time. A day later, my watch was no longer running slow; instead, it was gaining time. 🤦 I repeated this process every once in a while for about a year, never actually getting the timing to within a reasonable margin of error. The problem with my imprecise, unscientific, amateur approach to regulation is that if you only wait a few minutes to check the timing, it won’t have been long enough for any error to be apparent; if you wait a few days, there isn’t any instant gratification and you’ll probably forget about it until you realize your watch is several minutes out. At least, that’s how it went for me.

Professional watch people use a several-hundred-dollar tool called a timegrapher to precisely inspect a watch’s timing, letting them quickly make all the adjustments they need to make. I was thinking about this earlier today, after noticing that my watch was 7 minutes fast, when I realized that since watches tick audibly (listening to ticks with a microphone is in fact how timegraphers work), I probably didn’t need any specialized equipment to do this on the cheap: what if I just recorded the ticking and eyeballed it for accuracy, then adjusted the regulator accordingly? That would make for a much tighter feedback loop than my existing strategy.

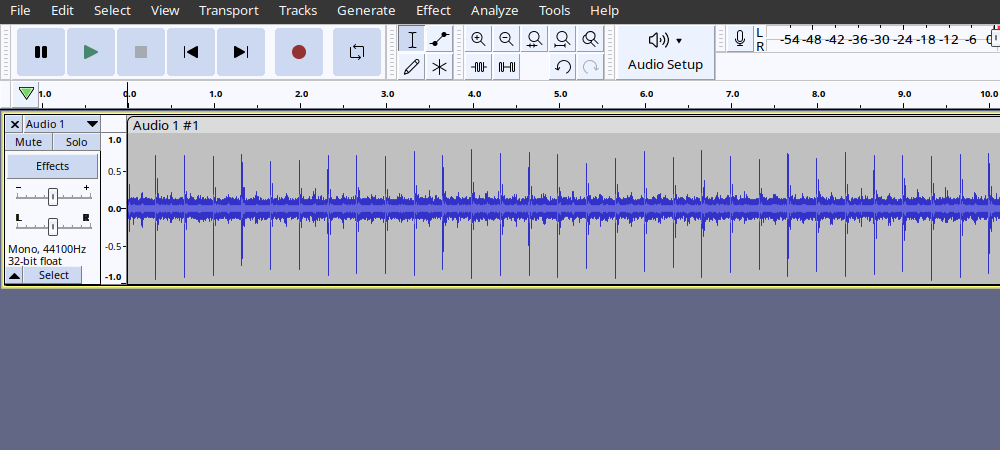

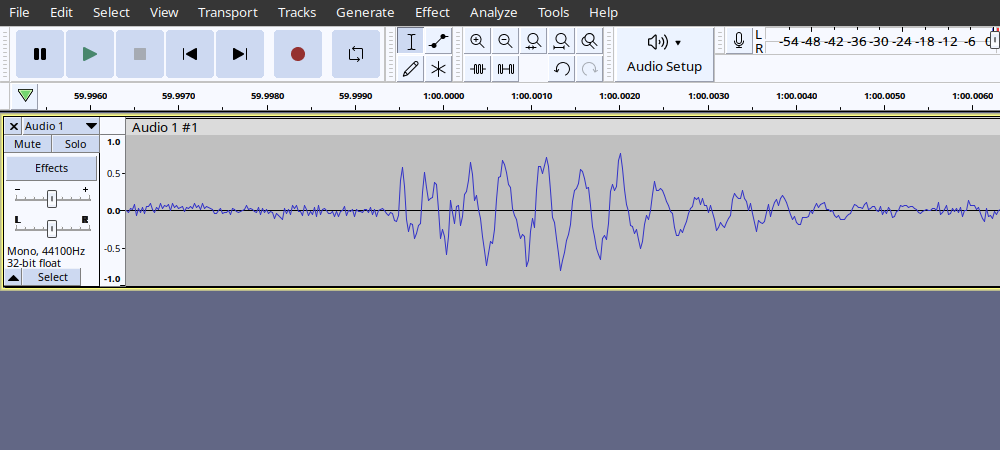

Using Audacity with a microphone-equipped USB webcam pressed directly against the back of my watch, I recorded a minute of ticking. I amplified the audio to be able to see it more clearly, then zoomed in to one of the ticks and deleted all the audio that came before it so that the tick lined up with the track’s zero-second mark. The 7S26C movement ticks at 21600 beats per hour, or 6 Hz, so with the timing properly regulated, a tick should fall precicely on every second. I scrolled to the end of my recording and zoomed in to the minute mark, then adjusted the regulator lever to compensate for the error. I partially screwed the case back back on to protect the movement, then took another recording. I repeated this process over and over again until I got the timing to within less than 1 millisecond out per minute, which should mean my watch will only gain about a second and a half per day; a much more tolerable amount. ⌚